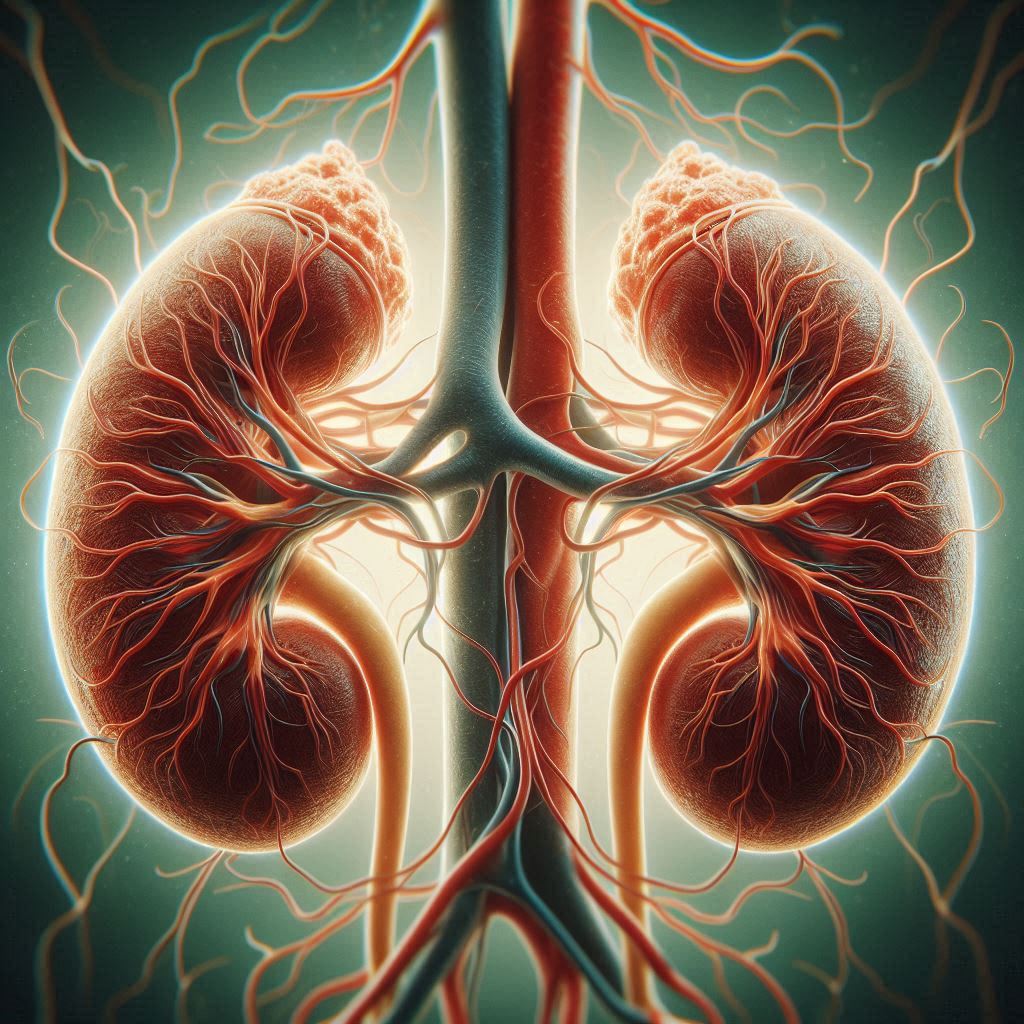

Definition

Gitelman syndrome (GS), also known as familial hypokalemia-hypomagnesemia, is an autosomal recessive renal tubular disorder that affects the kidneys’ ability to reabsorb sodium chloride (salt) in the distal convoluted tubule. This leads to excessive loss of electrolytes such as potassium, magnesium, and chloride in the urine, causing imbalances in the body. It is often considered a milder variant of Bartter syndrome but has distinct genetic and clinical features. The prevalence is estimated at approximately 1 in 40,000, making it one of the most common inherited renal tubular disorders.

Causes

Gitelman syndrome is primarily caused by mutations in the SLC12A3 gene, which encodes the thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride cotransporter (NCC) in the distal convoluted tubule of the kidney. Less commonly, mutations in the CLCNKB gene, which encodes a chloride channel, can cause similar symptoms. These mutations impair the kidney’s ability to reabsorb salt, leading to:

- Salt wasting: Excessive sodium and chloride loss in urine.

- Electrolyte imbalances: Low levels of potassium (hypokalemia), magnesium (hypomagnesemia), and chloride (hypochloremia), with low urinary calcium (hypocalciuria).

- Metabolic alkalosis: Increased blood pH due to loss of hydrogen ions.

- Hyperreninemia and hyperaldosteronism: The body compensates for salt loss by increasing renin and aldosterone levels, which can worsen potassium loss.

The condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, meaning both copies of the gene (one from each parent) must be mutated for the disorder to manifest. Carriers (with one mutated gene) typically do not show symptoms.

Symptoms

Symptoms of Gitelman syndrome typically appear in late childhood, adolescence, or adulthood (rarely in early childhood) and vary widely in severity, even among family members. Some individuals may be asymptomatic, while others experience significant symptoms. Common symptoms include:

- Musculoskeletal:

- Muscle cramps, weakness, or spasms (tetany).

- Paresthesias (tingling or prickly sensations, often in the face).

- In severe cases, paralysis or rhabdomyolysis (muscle breakdown).

- General symptoms:

- Fatigue and generalized weakness.

- Dizziness or lightheadedness, often due to low blood pressure.

- Salt cravings, sometimes accompanied by cravings for sour foods (e.g., vinegar, lemons).

- Gastrointestinal:

- Abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting (less common).

- Renal/Urinary:

- Increased thirst (polydipsia).

- Frequent urination (polyuria) or nighttime urination (nocturia).

- Joint-related:

- Chondrocalcinosis in adulthood, causing joint pain, swelling, or inflammation due to calcium deposits (likely from chronic hypomagnesemia).

- Cardiovascular:

- Low or normal blood pressure (hypertension is rare but reported in some adults).

- Prolonged QT interval on ECG, increasing the risk of ventricular arrhythmias or, rarely, sudden cardiac arrest.

Symptoms mimic those seen in chronic thiazide diuretic use, as the defective transporter targeted by thiazides is affected in GS. Severity can depend on the specific mutation, environmental factors, or gender (men may be more severely affected).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and, increasingly, genetic testing. Key diagnostic features include:

- Blood tests:

- Hypokalemia (low potassium).

- Hypomagnesemia (low magnesium, though not always present).

- Hypochloremia (low chloride).

- Metabolic alkalosis (high blood pH).

- Hyperreninemia and hyperaldosteronism (elevated renin and aldosterone).

- Urine tests:

- Hypocalciuria (low urinary calcium, a hallmark that distinguishes GS from Bartter syndrome).

- High urinary sodium, chloride, and potassium excretion.

- Genetic testing:

- Confirms mutations in the SLC12A3 gene (or rarely CLCNKB).

- Useful when clinical features overlap with other disorders like Bartter syndrome type III.

- Differential diagnosis:

- Bartter syndrome: Typically presents earlier, with normal or high urinary calcium and less severe hypomagnesemia.

- Surreptitious diuretic use: Can be ruled out with a urine diuretic assay.

- Laxative abuse or vomiting: Low urinary chloride levels (<20 mmol/L) distinguish these from GS.

- Hypokalemic periodic paralysis: Involves intracellular potassium shifts rather than total body depletion.

Diagnosis may be incidental during routine blood tests showing hypokalemia or metabolic alkalosis. A thorough family history and exclusion of other causes are critical.

Treatment

There is no cure for Gitelman syndrome, but treatment focuses on correcting electrolyte imbalances and managing symptoms. Management is individualized based on symptom severity and biochemical abnormalities. Common approaches include:

- Electrolyte supplementation:

- Potassium: Oral potassium chloride (KCl) to correct hypokalemia. Large doses may be needed due to ongoing urinary losses.

- Magnesium: Oral magnesium supplements (e.g., magnesium oxide, magnesium sulfate, or magnesium chloride). Magnesium chloride is often better tolerated, as others may cause diarrhea. Intravenous magnesium may be required in severe cases.

- Dietary modifications:

- High-sodium diet to counteract salt wasting.

- High-potassium foods (e.g., bananas, oranges) to support potassium levels.

- Medications:

- Potassium-sparing diuretics (e.g., amiloride, spironolactone) to reduce potassium loss.

- Rarely, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors or anti-aldosterone therapy to manage refractory hypokalemia.

- Monitoring:

- Regular follow-up with a nephrologist (at least annually) to monitor electrolytes, kidney function, and symptoms.

- Cardiac screening (e.g., ECG) to assess for prolonged QT interval or arrhythmia risk.

- Lifestyle:

- Patients are encouraged to self-monitor symptoms and adjust supplement doses if unwell (similar to diabetes management).

- Avoid triggers like dehydration, excessive exercise, or electrolyte losses from vomiting/diarrhea.

Treatment during pregnancy requires close monitoring, as symptoms may worsen. Intravenous potassium or magnesium infusions may be needed in severe or resistant cases to prevent hospital admissions.

Prognosis

The long-term prognosis for Gitelman syndrome is generally excellent, especially with proper management. Most patients lead normal lives, though some experience reduced quality of life due to fatigue, muscle cramps, or chondrocalcinosis. Rare complications include:

- Chronic kidney disease (limited data on long-term risk).

- Cardiac arrhythmias or sudden cardiac arrest (rare but warrants screening).

- Growth delay in children with severe hypokalemia/hypomagnesemia.

Asymptomatic patients may only require annual monitoring without active treatment.

Additional Notes

- Overlap with Bartter syndrome: Gitelman syndrome was historically considered a subset of Bartter syndrome, but distinct genetic causes (SLC12A3 vs. other genes) and clinical features (e.g., hypocalciuria in GS) differentiate them.

- Genetic counseling: Since GS is autosomal recessive, there’s a 25% chance of recurrence in siblings of affected individuals. Genetic testing can identify carriers in families.

- Research gaps: Long-term outcomes, optimal diagnostic criteria, and the impact of therapy on quality of life require further study.

Disclaimer: owerl is not a doctor; please consult one..

Leave a Reply